Miep Gies

It is 4.40pm on the afternoon of March 25th 1996 in Los Angeles and a white stretched limousine is stuck in traffic. Lost in the back seat, a small, bespectacled, elderly, grey haired lady smiles wistfully. By her standards, total gridlock and a journey that normally takes 30 minutes, but which is now likely to be 3 hours, doesn’t even rate mention on the anger or frustration scale.

Even so, this isn’t just an ordinary traffic jam, for every vehicle as far as the eye can see is a stretched limo. In fact it is limo-lock, the predictable result of every gargantuan gas guzzler from LA, San Diego, Las Vegas, and even San Francisco, being enlisted to ferry folk to the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in downtown LA for the 68th Academy Awards Ceremony.

At this annual celebration of self congratulation, tears and glamour, clearly no self respecting member of Hollywood’s glitterati can be seen dead in a set of wheels that couldn’t accommodate the residents of a small city, or at least a decent sized Jacuzzi, so the consequential mess of stationery vehicles is something to behold. You don’t see that on tv.

But you do see Clint and Julia and Mel, and of course Jack in his trademark sunglasses, and they are all looking great in their Armani and Valentino and Dior, and they are all descending, or is it ascending, on the red carpet. The tiny granny in her off-the-peg neat black suit and string of pearls passes un-noticed into the auditorium. No one knows her and fewer care, yet had they known who she was they would certainly have mobbed her, requesting photos and autographs as they do with the most celebrated Hollywood star.

Miep Gies, for it is she, is not a name that trips easily or knowingly off the Anglo Saxon tongue, but in her lifetime, which ran to more than a century from February 1909 to last Monday evening, she became an historical figure of considerable importance. By her many daily acts of selfless bravery, and one enormous act of what turned out to be massive foresight, this Viennese born Catholic of small stature but giant courage came not only to symbolise the best, most noble side of humanity, but she also gave us one of the most iconic and widely read books of non fiction of all time.

Between July 1942 and August 1944 Gies was one of a group of 5 people who provided aid and sustenance on a daily basis to 8 Jews in hiding in the top two floors of a secret annex of an Amsterdam office building, as memorialised in the writings of the youthful diarist, Anne Frank. On a sunny morning in August 1944, Anne, her parents, sister and the others from the hiding place were arrested by the Gestapo. After they had been taken away Miep and a colleague entered the sealed, no longer secret hiding place and instantly spotted a mess of loose hand-written papers, several school exercise books, and a red plaid diary scattered on the floor.

Collectively these represented what we have today come to know as the diary of Anne Frank. They had been tossed to the floor by the Frank’s arresting officer so that he could use the briefcase that held them to carry away valuables collected from the prisoners’ possessions. He was not to know that one day by far the most valuable item of all would be the work that he had so unceremoniously discarded on the floor. Miep gathered all of the papers and books together and placed them unread in the top drawer of her desk in the expectation, or was it perhaps simply the hope, that she would give them back to their rightful owner when Anne returned home after the war.

The rest of the story we surely know: Anne, like so many, did not return. In fact of the 8 sheltered by Miep, her husband, and her colleagues for those 25 long months between the summers of 1942 and1944, only Anne’s father Otto survived. Here are a shattering set of facts that place this in context: 104,000 Jews, more than 75% of Holland’s pre-war Jewish population, were deported to concentration camps elsewhere in Europe during World War Two. Of the 60,000 or so who, like the Franks, were sent to Auschwitz, only 673 were to return alive. Of the 34,313 sent to Sobibor, just 19 came back.

The names of most of these victims, like those from all over Europe, will never be known, but Anne Frank was spared that anonymous fate through her “voice-from-the-grave” entries on those pages collected from the floor of the attic on August 4th 1944. Now, with Miep Gies’ death, the last living connection to the diary is gone.

I asked Miep as we sat in the limo in Los Angeles about how she felt about the paradox that her acts of kindness and courage all those years ago in such dangerous circumstances – sheltering Jews was after all a capital offence – had now led to this strange, equally unreal Hollywood circus. She gave one of her wistful smiles and said in her heavily accented, slightly halting English: “Anne always wanted to be a famous writer. She loved Hollywood and wanted to come here. She never managed it, so the only reason I have come is for her.”

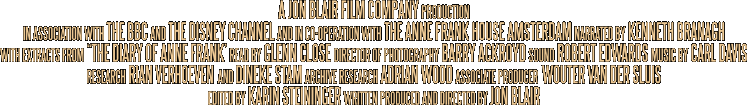

I took Miep up on stage with me to collect the Academy Award for my film Anne Frank Remembered. I explained who she was, and said something along the lines that in this city of celluloid heroes here was the real thing. I also told the audience of stars in the theatre the story of what she had said in the car on the way to the ceremony, and, as one, they rose to their feet to give her a lengthy standing ovation. Yes, even Jack in his shades stood up. She made to say something but to my eternal shame I hushed her, fearing that she would suffer the indignity of the orchestra drowning out her words, as is the form when those at the microphone have out-stayed their welcome.

When I was making my film about Anne, Miep showed me the relics she had retained from those years: a shawl of Anne’s, a shopping list of groceries, a ring given to her by Mrs van Pels. In themselves prosaic items, but vested as they were with the symbolism of the memory of her now long dead friends, they had a weight about them that was almost unbearable. For these were the treasured objects of a woman who had devoted the very large part of her long adult life to perpetuating the memory and legacy of a child she had once sheltered and befriended.

And there is another child in this story, someone whose existence Anne never mentioned and probably knew nothing. Peter Pepper as he styled himself on emigrating to the United States in the 1950’s, was the son of Fritz Pfeffer, the middle aged dentist who shared Anne’s bedroom in captivity. It was Pfeffer to whom she gave the nom de plume of “Dussel”, which is the German for “idiot”, and for whom she reserved the most splenetic and vituperative of her extensive vocabulary of disdain and loathing. Little did she know that Pfeffer had a son, Werner, two years older than herself, whom he had sent to England from their home in Berlin just after Kristallnacht in November 1938. Pfeffer was never to see or hear from his son again.

Werner became Peter and a successful businessman in California, but he kept his distance from the whole Anne Frank business, never quite forgiving the girl for her unflattering portrayal of his loving father. However in 1994 I persuaded him to come to Amsterdam to visit the hiding place of his father and the others for the first time. There in the same bedroom that his father had lived with the teenage writer I introduced him to Miep whom he had never met.

Fritz had been Miep’s dentist, and, desperate for help in late 1942, he had turned to her, asking if she knew anywhere he could hide. She in turn had asked Otto Frank if there was room for one more in the annex, and then for the next year and a half until they were all captured, she sustained him, not only with food, but by carrying letters back and forth to his non Jewish fiancée. For the lonely man, shorn of his own family while surrounded by two other family groups and sharing a bedroom with a difficult adolescent girl, this contact that Miep gave him with the outside world and with someone whom he loved and loved him, must have provided unimaginable support.

I filmed the one and only meeting between Miep and Pfeffer’s by now middle aged son, as tearfully he thanked her for what she had done for his father. It was rare in my experience that she was lost for words, but here in the actual room in the hiding place which Anne and Pfeffer had shared 50 years previously, and faced with this man/boy who bore a striking resemblance to his father, wiping away his tears of embarrassed emotion, all she could say of Pfeffer/Dussel was: “He was a lovely, lovely man….and a very good dentist.” Two months later Peter died of cancer.

In the hiding place, for her part, Anne confided in no one except the imaginary “Kitty” of her diary, but she seemed to trust Miep. There was one occasion however, in July 1944 just weeks before the hiding place was raided, when the helper stumbled in on the girl while she was writing her diary and saw a different side of her. Later she was to say of this encounter: " Over the years I’d seen Anne, like a chameleon, go from mood to mood, but always with friendliness. She’d never been anything but effusive, admiring, and adoring with me. But I saw a look on her face at this moment that I’d never seen before. It was a look of dark concentration, as if she had a throbbing headache. This look pierced me, and I was speechless. She was suddenly another person there writing at the table. … Anne stood up. She shut the book she was writing in and, with that look still on her face, she said, in a dark voice that I’d also never heard before, “Yes, and I write about you too.”

She continued to look at me, and I thought, I must say something; but all I could say, in as dry a tone as I could muster, was “That will be very nice.””

Miep respected, understood and sympathised with this difficult child, caged as she was like a bird. When Anne demanded news of the outside world from her, Miep gave it, uncensored and without pulling any punches about some of the most terrible events imaginable. When Anne outgrew the shoes she had had when she went into hiding, Miep provided a set of high heels, the only ones the girl ever owned. Miep was kind and she was brave, without ever thinking that she was either.

There was also a time early on in the whole saga when she and her husband shared the hiding place for a night after the annex occupants, and especially Anne, had insisted they give it a go. She said later that more than anything this drove home to her how terrifying the situation was for those in hiding: “I never slept; I couldn’t close my eyes. I heard the sound of a rainstorm begin, the wind come up. The quietness of the place was overwhelming. The fright of these people who were locked up here was so thick I could feel it pressing down on me. It was like a thread of terror pulled taut. It was so terrible it never let me close my eyes. For the first time I knew what it was like to be a Jew in hiding.”

Then I remember her telling of her devastation when the family was arrested, of how she then went to the Gestapo headquarters where they were being held in a vain attempt to bribe the Nazis to release their newest prisoners. She would have been 35 at the time, and just over 5 foot tall, yet she went right up to these Germans in their jackboots and their caps emblazoned with the skull and cross-bones, making it clear that she would offer them cash for souls. Telling this story 50 years later it was clear that it was as vivid for her as if it had happened yesterday. She had told it often enough, but as she described stumbling in on the SS men listening to the BBC news from London on a radio in their office, and her subsequent ejection from the premises, feeling, as she put it, that “The curtain of this play had fallen”, I could feel her utter dejection and sense of failure and loss, undiminished by the years.

For this was a woman who did not believe in heroics, let alone seeing herself as any sort of hero. She simply did her duty, whatever that might require. So, when as the years went on, Anne’s diary became more widely known than its late author could ever have imagined in her wildest dreams, and Otto Frank determined that his daughter’s words should be used to foster a message pointing out the dangers of anti-Semitism, racism and discrimination, it was only natural that Miep should throw herself behind this campaign.

After Otto’s death in 1980, and particularly after the death of her husband in 1993, she became the most prominent ambassador for the diary and its “message”, travelling the world speaking at schools, churches, synagogues and community centres. She was showered with awards from the Netherlands, Israel, Germany and her native city of Vienna. Only on August the 4th each year she refused to leave her home as she contemplated the anniversary of the day in 1944 that all the efforts of her and the other protectors turned to nought.

After her 1998 stroke she had to stop all the travel and she said she missed it. I know she had her son and her grandchildren around her but beneath the surface of this modest, self-effacing grandmother, was a woman who, whisper it quietly, I think enjoyed the bigger stage that being Anne Frank’s protector had given her.

I once made a documentary about Oskar Schindler, ten years before Spielberg’s biopic, but I don’t think I ever really came to grips with the motives for why he did what he did. With Miep it was a simpler affair. Here was someone grounded in notions of what was right and what was wrong, in the idea that someone should strive to do “the right thing”. It didn’t need thinking about. One just did it.

Then there was the fact that she held her employer, Otto Frank, and his family, in the highest regard. She was devoted to him. There was never any question, therefore, of her ever answering in any way other than in the affirmative when, as the Nazi vice tightened around Holland’s Jews and he asked for her help in preparing the hiding place, and then subsequently in sustaining them while they stayed hidden behind the now famous book-case.

This last however could have played no part in the decision she and her husband made to hide an anti Nazi student in their flat, in addition to their dangerous roles as the protectors of those in hiding at her office premises. When I asked about this she simply said she couldn’t turn him away knowing what his fate would be if she did nothing to help him.

Miep was Schindler’s antithesis in every respect, yet ironically they are both bound together by their common, yet so uncommon, achievement. They were rescuers at a time when rescuers were few and far between.